Yurts Go Way Back

I am delighted to share a very special guest post today: Candace Rardon is a brilliantly talented artist and yurt enthusiast. She posted this illustrated history of yurts on her blog and has given us permission to share it here.

Candace's beautiful sketches make her informative post charming and fun to read. Check out her blog for more of her beautiful artwork, especially this "Day in the Life of a Yurt Dweller" post.

I hope you enjoy Candace's post as much as I did!

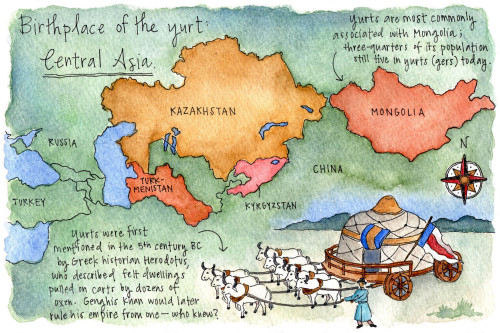

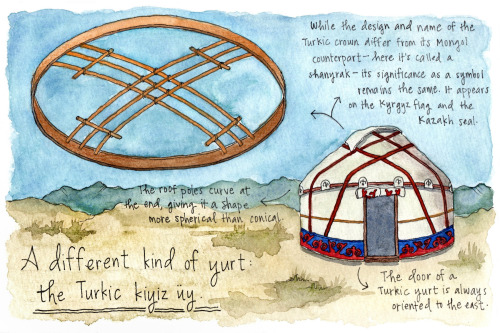

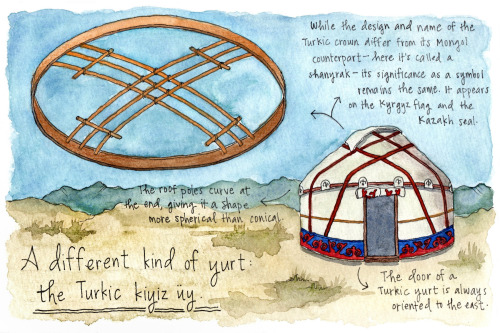

The first thing I was surprised to learn was that the word ‘yurt’ itself, the term most commonly used by Westerners, is actually Russian in origin, while Mongolians have their own word for their felt-walled home – ger. And in Turkic nations such as Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, yurts are called kiyiz üy, which translates as ‘felt house.’

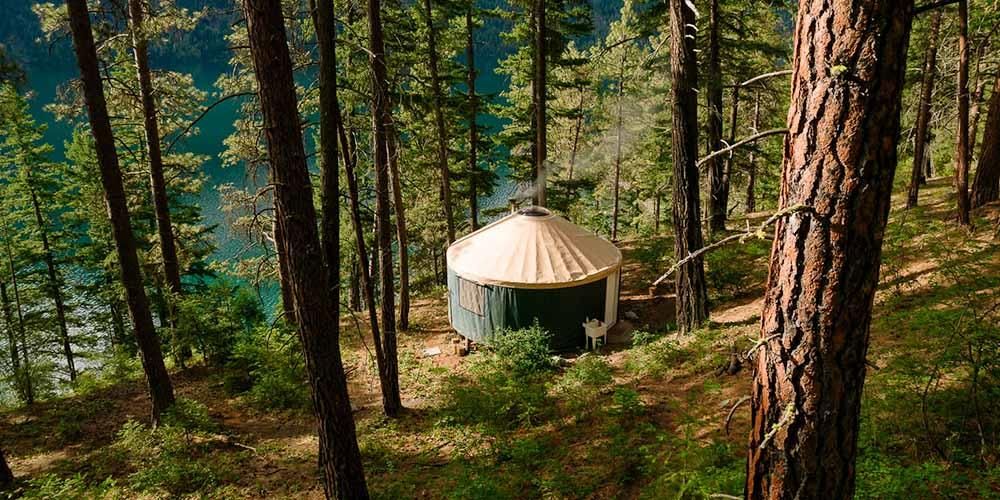

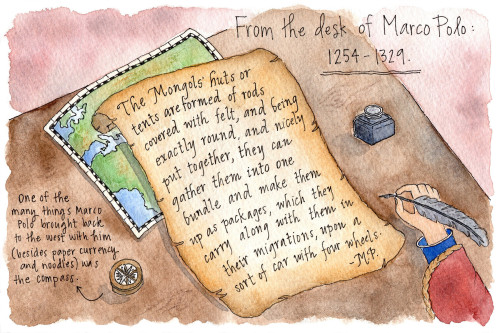

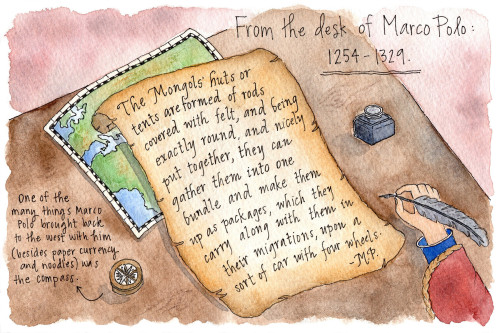

All of these people groups are traditionally nomadic. Both the wild animals they hunt and the domestic livestock they raise – herds of cattle and camels, sheep and goats, and especially horses – necessitate a pattern of migratory movement for fresh grazing. The term ‘nomad’ itself even comes from the Greek word for pasture, nomos. They move at least twice a year but often more, shifting with the seasons, lifting and lowering their light round homes in as little as 45 minutes.

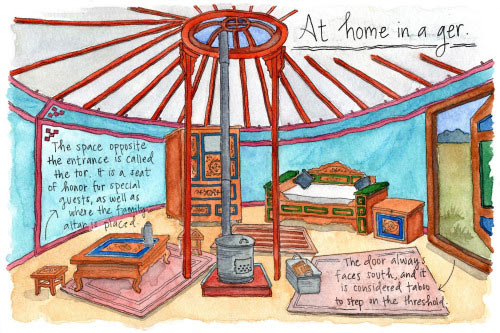

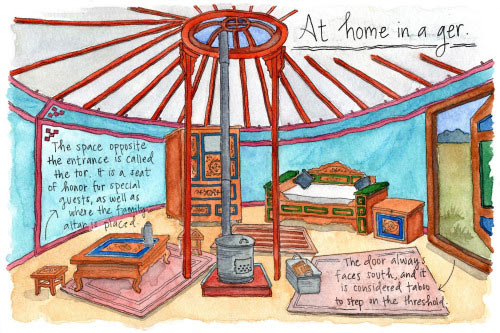

I was also surprised to learn that Mongolians are quite superstitious, and that they have all sorts of rituals and taboos and beliefs governing life in a ger. Instead of knocking, you should call out “Nokhoi khor,” which translates as “hold the dog,” and bow your head before entering – even if no one’s home. You should walk around the ger clockwise, from left to right, following the path of the sun. You shouldn’t lean against the walls or support poles, as these are symbols of stability, and if you stay the night, you should sleep with your feet pointing towards the door.

The list goes on, but what intrigued me even more than the taboos themselves was the reasoning behind them – the fact that yurts hold a great amount of meaning for the families who call them home.

“The Ger is more than their traveling shelter on the Asian steppes,” one article says. “It is their centering point in a moving universe.”

I am a lover of symbols – for objects that have one meaning, but point towards another layer of meaning beneath them. For Mongolians – and for other tribes of Central Asian nomads as well – the yurt seems to be such a symbol.

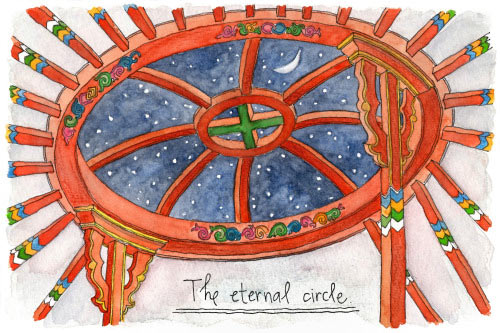

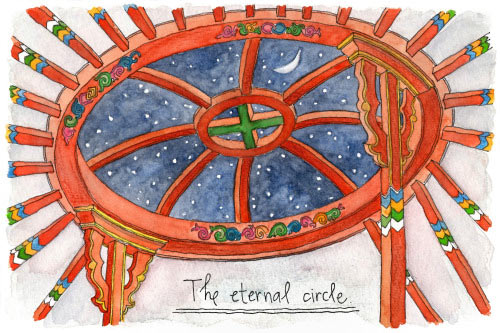

“Nomadic life is marked by eternal circles,” writes Alma Kunanbay in the same Smithsonian essay I mentioned earlier, “the circle of the sun, the open steppe, the circumference of the yurt, the horned circular scroll of ornaments…The completion of one circle leads to the beginning of the next.”

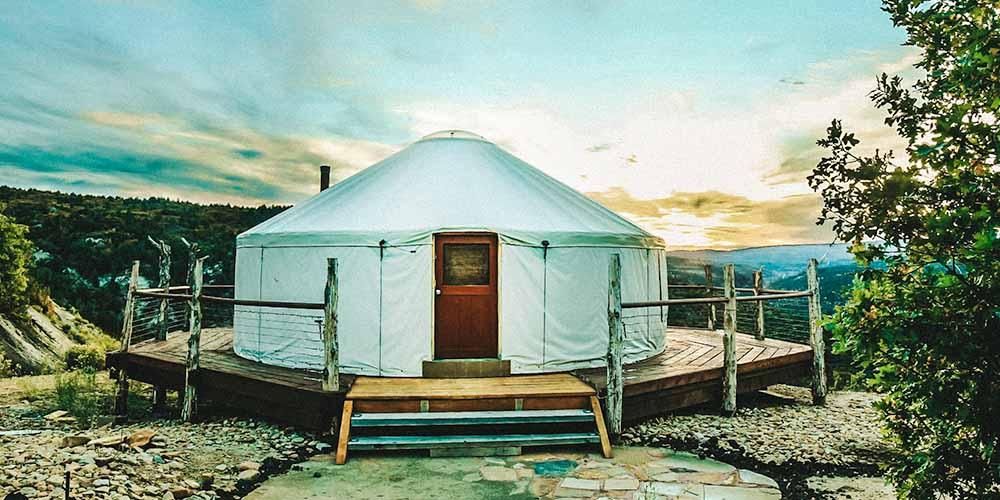

Before diving into my first vortex of research last week, this was something I’d already observed about my own experience of yurt living – how it’s really a series of concentric circles: from the circle of Salt Spring (an island that isn’t quite circular, but still) to the circle of fir and pine trees surrounding my yard to the circle of the yurt itself, endless layers of rings ever narrowing like an hourglass to their connecting apex – the fishbowl bubble of a window in the roof. And it’s there that it all begins to widen again, from the circle of the globe window to the greater globe of the sky above.

Sitting here beneath the window now, I find it has an almost spiritual effect – the bowed glass forever pulling at your gaze, your eyes magnetically drawn to the billowing clouds and branches and, at night, the pure panoply of stars and occasionally the moon itself. Even the yurt’s roof poles, all angled towards the window in perfect parallel lines, seem to say the same thing: look up, look up, look up.

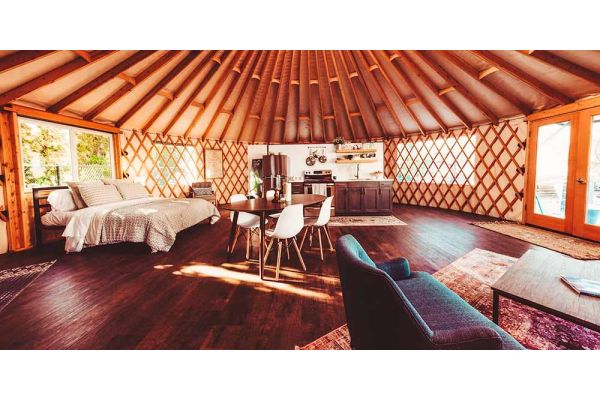

And so what I was most thrilled to learn last week is that when it comes to my obsession with the circle at the center of my roof, I’m rather late to the game – that Mongolians and their Turkic neighbors have always placed a special amount of significance on the crown of their homes.

Instead of a plexiglass bubble, they have a carved wooden ring called a tono, or shanyrak in Turkic, which acts as a smoke hole. While the rest of the yurt may be replaced – the willow lattice walls, the roof poles, the felt – the crown is passed down for generations, typically from father to youngest son. “It is a symbol of home and family and represents an opening up to the world,” writes this article.

While my own crown is considerably less decorated than its Central Asian counterpart, it still serves the same purpose. It serves to bring the outside world in, while at the same time bringing me to a deeper sense of connection with the world.

It is this blurring of worlds I will miss the most when it comes time to leave Salt Spring – an eternal circle I will endeavor to keep living under, no matter where I call home next.